Janwaar Maker Space in the Making: Seeed’s Open Source Hardware for Rural Changemakers’ Self-Empowerment and Social Inclusion in India

By Ye Seong SHIN 3 years agoIn an effort to assist decentralization of digital education for rural children in India, Seeed donated open hardware products to Janwaar village, where the children and youth were inspired to learn coding and programming for the first time in their lives. Through embracing the learning principle of hands-on, DIY, and collaborative learning, they were self-empowered to have the ownership of technological tools, and to tackle gender inequality and casteism at village level. On this backdrop, this “Janwaar Maker Space in the Making” Project directly or indirectly accelerates the UN’s SDGs 4, 5, 10, 11, 9, 1, 17, 8 and 16.

Project Name: “Janwaar Maker Space in the Making” Project

Deployment Location: India

Targeted Industry Type: STEAM Education

Project Partner(s):

Global projections indicate that India will be the most populous country by 2024, and the world’s third largest economy by 2050 (Pande, 2020). However, in order to unleash India’s potential to rise up as a global powerhouse, many scholars opine that a myriad of socio-economic and environmental challenges should be aptly addressed. Among other things, these challenges include: i) elimination of extreme poverty, gender inequality and patriarchy; ii) promotion of women’s empowerment, and; iii) augmentation of national literacy rate (Mann, 2021). Even though India’s National Education Policy 2020 sheds light on promoting digital learning as an alternative education model to the traditional, classroom-based education (Sardana, 2021), the effectiveness of this policy implementation in rural villages remains questionable to date.

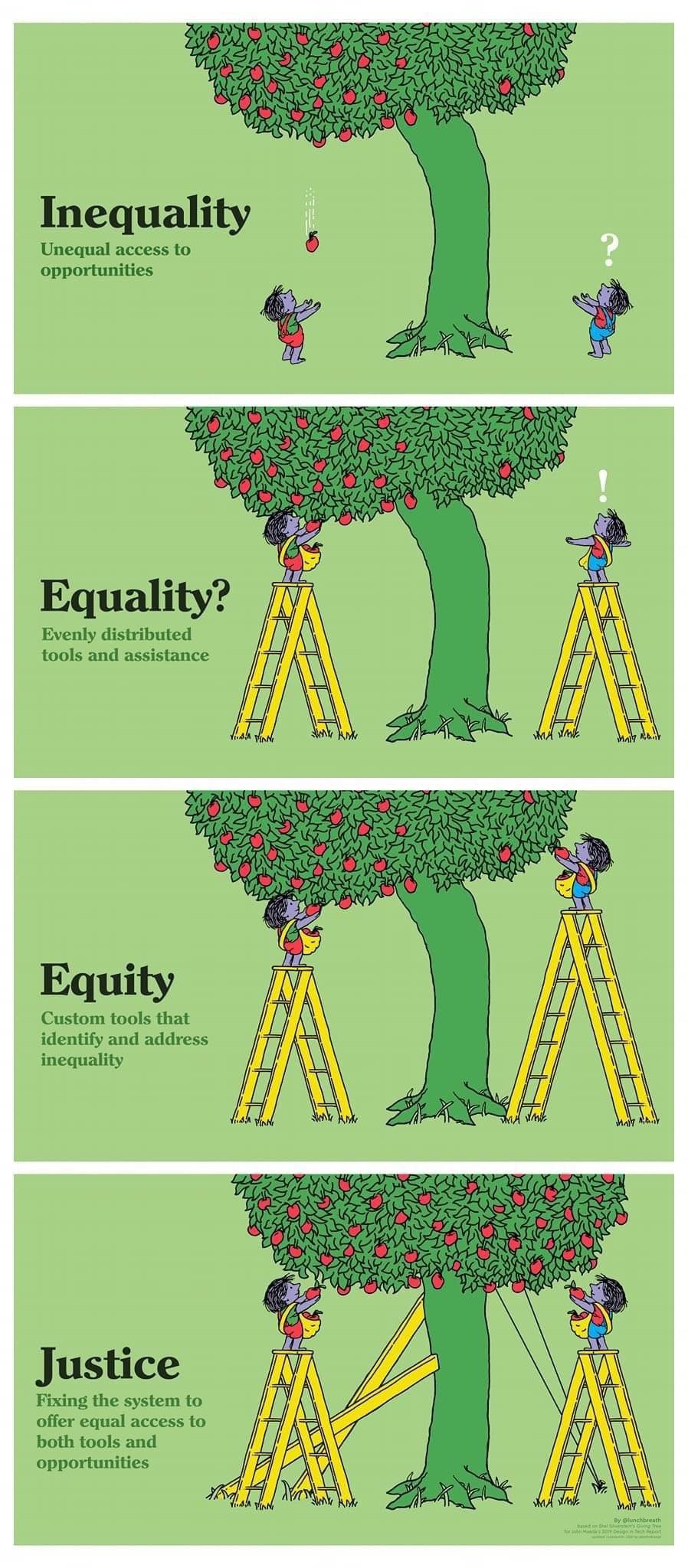

Reportedly, India has 664,369 villages, in which approximately 700 million people are living – representing 60-70% of the total population (TEDx Talks, 2017). According to Saxena (2021), national agricultural development programs from the 1960s have benefited only those who were privileged, and a series of rural reforms “only reshuffled the power structure”. These efforts were clearly not efficient enough to change everyday life conditions of the most underprivileged population groups. (Saxena, 2021). When it comes to educational programs designed for villages, they were not successful because “… most of these programs – they have clearly-defined outcomes. They are designed like ready-to-use products. They fail, because they are for the villagers, not with the villagers. They fail because they’re based upon this distinction of those who know, and those who [should] be taught.” (TEDx Talks, 2017). Now, this makes us ponder about what exactly is equality, equity, and justice in our world (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Equality, Equity, and Justice

ⓒ Tony Ruth (@lunchbreath on Twitter)

What’s the Challenge?

How to effectively democratize digital education for children in underprivileged rural villages?

What’s the Project About?

In 2019, in order to decentralize and democratize technological education for village children in India, Seeed Studio donated open source hardware products to children at Janwaar. With the products, the children came together to self-teach and explore the world of open tech, coding, and programming for the first time in their lives (Figure 2). As a result of this initiative, children are inspired to make their own maker space in the community.

Figure 2. Children at Janwaar Castle Exploring Seeed’s Open Tech Products by Playing

ⓒ Anil Kumar

Janwaar Castle is a skatepark (first rural skate park in India!) in a small rural village of 2,000 inhabitants called “Janwaar”, which is located in Bundelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh Province of India (Figure 3). At the village of Janwaar, it has a community center called “Villa Janwaar”, which is fully run by the rural children representing 2 organizations: Barefoot Skateboarders Organization, and The Rural Changemakers. Janwaar Castle and Villa Janwaar are learning platforms in which the village children are encouraged to participate in workshops on skateboarding, music, arts, dance, painting, sports, agriculture, English language, and general life-skills. (India 101, 2016; World Orgs, n.d.; Prema, 2021).

Figure 3. Everyday Landscape of Janwaar Castle ⓒ Janwaar Castle & Villa Janwaar

(Janwaar Castle, n.d.)

Janwaar Castle was founded by Ulrike Reinhard (Figure 4), who is a German publisher, writer, digital advocate, and futurist. She has also been an editor of WE Magazine and has written articles for Think Quarterly. (Narayanan, 2015; Netzspannung.org., 2017).

Figure 4. Ulrike Reinhard

ⓒ Aslam Saiyad

In April 2015, the skatepark was opened to the public after 3-months of avid construction on 1.2 acres of land. Naturally, village children became curious about what was being built, and unknowing what exactly the skatepark was about, they started using it as a slide to play (Figure 5). When the children were given 20 skateboards, there were neither teachers nor instructors. As Ulrike describes, the children surprisingly learned skateboarding fast, based on the principle of self-learning or DIY. As the children started to learn by themselves, teams were built suddenly (or most naturally), older children were helping out younger children, and better-skilled ones were sharing their knowledge with less-skilled ones. All of these witnesses boil down to the essence of collaboration, peer learning, and co-creation in practice, while overcoming social prejudices. The skatepark brought fun to the everyday lives of children, as Ulrike describes, skateboarding was what “fueled children with positive energy and self-confidence”. (TEDx Talks, 2017).

Figure 5. Children Going Down a Slide When the First Skate Slope Was Constructed

ⓒ Janwaar Castle & Villa Janwaar (TEDx Talks, 2017)

Ulrike’s vision of the skatepark was to facilitate self-empowerment and self-confidence of children in rural India by introducing skateboarding. This, for children, was a meaningful activity to enrich their lives and learn new skills by playing, but with 2 rules: “No School, No Skateboarding” and “Girls First”. As a result, the village of Janwaar has received numerous national and global spotlights on transforming a quiet rural village into a lively, healthy, and inspirational community of skateboarders through transcending casteism and gender inequality. Currently, Janwaar village has a second skatepark, which is bigger than the first one and is located right next to the community center. Ulrike shared in her speech (TEDx Talks, 2017):

“Janwaar, like any other villages in India, is strictly divided by castes [Adivasi and Yadav]. … There’s hardly any interactions between them. … Building a skatepark might seem like, … a simple intervention. But it quickly turned out to be much, much more. This skatepark has [brought] the village into life, it has broken taboos, it has [broken] down barriers, and it has become a trigger for really sweeping far-ranging [social, cultural and economic] changes.”

At some point in time, the need for digital education was strongly felt by the children at Janwaar Castle. In fact, the children never saw a computer until 1.5 years ago, nor did they have any proper education on computing. Therefore, in 2019, we happily decided to send the children our simple-to-learn open source hardware products to foster STEAM education on coding and programming. Since the children were used to DIY-learning, peer learning, and collaborative hands-on learning principles, and that they were self-empowered to explore the unknown, it was no surprise that they instantly got excited over the new open tech tools to play with. The Seeed products that we sponsored for Janwaar Castle were:

- Grove Beginner Kit for Arduino (Learning kit for Arduino beginner and STEAM educators)

- Glint Programmable Wearable Bracelet (Wearable learning kit for children)

- Grove Zero Car Kit V2.0 (Automated car kit to develop mathematical, problem-solving, and programming skills and knowledge)

- Arduino Uno Rev3 (A microcontroller board based on ATmega328, an 8-bit microcontroller with 32KB of Flash memory and 2KB of RAM)

- micro:bit Telec version (Micro:bit is a pocket-sized microcontroller designed for children and beginners to easily learning how to program, build DIY digital games, and create interactive projects)

- BitWearable Kit (Designed for micro:bit beginners and others who want to customize their smart toy watches)

Now, what is the first thing that we need if we want to try out the open tech gears? Correct, electricity. Since the only place in the village where there is solar-powered 24/7 electricity (thanks to Ulrike) is the community center, i.e., Villa Janwaar, open tech workshops on the products sent by Seeed was held there. By then, the only person who had received some sort of computing lessons in the village was Anil Kumar – a 16-year-old changemaker living in Janwaar (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Anil Kumar with His Skateboard and Village Children

ⓒ Arun Kumar

In fact, Anil is a village child himself, and has been actively participating in an inclusive education program called “Open School Project”, which provides formal education opportunities for rural children in underserved areas. It was this program, where he picked up English language and basic computing skills. Therefore, Anil was the perfect trainer at Janwaar to teach open tech for the rest of the children at the community center. Even though he may not be the open tech professional, Anil was trying his best to convey his knowledge, application scenarios, and amazing potential of open tech for children, which was enough for them to be empowered and motivated to continue this initiative further. How did Anil make this workshop possible? Because he is a natural-born Maker at heart! Let’s take a look at Anil’s reflective learning journal:

“We did our sessions in the community center, where we have all the required gadgets. When I was conducting sessions on hackerspace, around 15 to 20 kids were coming, and sometimes there were more. … All kids belong to Adivasi and Yadav caste, and of course, from poor families. … I take computer sessions in order to make the kids familiar with the computer. I do it in a way that is interesting for them and easy-to-learn. They play various games from which they get to learn something like – maths, English alphabets. … smaller kids learn from the games. My objective has always been that whatever I know, I could pass on my learning to the other kids in the best way that I can. The outcome is that the kids now know how to attend a meeting [on-site], and they attend their online sessions by themselves. They are learning computers by playing.” (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Children at Janwaar Castle Playing with Seeed’s Open Tech Tools

ⓒ Anil Kumar

Anil goes on sharing that:

“My reflection of using Seeed’s product was great. … The happy thing was that the kids really enjoyed working with the car and glint kit and we figured out how to run it. … In the future, I would like to learn together with the kids about the gadgets more, and then we all can think what else we can do with them. It would be great if we, the kids, get introduced to them and learn about their functions better. Only then, I think we could make something, really good output, which can be anything. This is the one thing that I, as a kid, thinks, and if you have any suggestions you can also help us.”

Yes, there is a maker space in the making at Janwaar. Yes, Janwaar is filled with aspiring leaders of India’s tomorrow. Yes, Seeed Studio is rooting up for the children’s bottom-up innovations using open tech. As Ulrike highlighted in her speech (TEDx Talks, 2017),

“We do believe that only when you put all stakeholders of the village together, then you can not only trigger but [also] really drive sustainable change – change, which is carried out by the villagers themselves, because it’s them, who have initiated this.” (Figure 8)

Figure 8. Janwaar’s Changemakers Skating Together

ⓒ Janwaar Castle & Villa Janwaar (TEDx Talks, 2017; Janwaar Castle, n.d.)

Which SDGs Are Relevant?

Today’s “Janwaar Maker Space in the Making” Project showed us how a simple intervention like skateboarding and introduction of open tech tools can change the lives of rural children forever. In order to better understand impacts of this Project, it is necessary to take a look at the following SDGs (Figure 9):

Figure 9. “Janwaar Maker Space in the Making” Project’s Contribution to SDGs (UN, 2016)

In an effort to grasp what these SDGs signify, their specific Targets should be reviewed, and only then, can we realize the overlapping and symbiotic relationship of the SDGs:

- Make sure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education, and that all women are men have access to technical education and vocational trainings for decent jobs and entrepreneurship (Targets 4.1, 4.3, 4.4)

- Eradicate gender disparities in education and vocational training for children in vulnerable situations, including using ICTs to facilitate self-empowerment of women (Targets 4.5 & 5.B)

- Eliminate all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere, including but not limited to women’s full and effective participation for leadership, and equal access to ownership of properties (Targets 5.1, 5.5 & 5.A)

- Empower and promote social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, origin, ethinicity, economic background, or other status (Target 10.2)

- Provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible public spaces, in particular for women and children, while fostering positive socio-economic, and environmental bonds between urban, peri-urban and rural areas (Targets 11.7 & 11.A)

- Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure to support human well-being, with a focus on equitable access for all, such as ICT development and innovation capacity (Targets 9.1, 9.B & 9.C)

- Eradicate extreme poverty by ensuring that all vulnerable people have equal rights to ownership and control over new technologies (Targets 1.1 & 1.4)

- Promote resource mobilization through development cooperation at domestic and international levels (Targets 1.A & 17.1)

- Greatly decrease the proportion of youth in education by fostering productive activities, creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship (Targets 8.3 & 8.6)

- Promote North-South, South-South and triangular regional and international cooperation on science, technology and innovation knowledge transfers, along with sharing environmentally-sound technologies (Targets 17.6, 17.7 & 17.9)

- Augment global partnership for sustainable development through multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources (Targets 17.16 & 17.17)

- Guarantee responsive, inclusive, and participatory decision-making by giving access to information and protecting fundamental freedoms (Targets 16.7 & 16.10)

Indeed, children at Janwaar Castle showed us an exemplary case in point of a locally-driven innovation system. As Prof. Rajesh Nair notes, small maker spaces in communities for children and youth can facilitate learning on designing and fabrication of technological gears. After learning the fundamentals, they will be enabled to brainstorm possible solutions to the challenges they are facing locally. Afterwards, with further developments, the children would be able to make the solutions into real-life products, with which they can become new entrepreneurs in this bottom-up innovation ecosystem, and later contribute to the society they are living in, while rising up from the extreme poverty gap. (Nair, 2020). Ulrike makes an analogy of a well-known proverb (“It takes a village to raise a child”) to her strong and positive belief in the potential of the village of Janwaar: “It takes the children to transform a village” (TEDx Talks, 2017).

About Author

Ye Seong SHIN

Sustainability and CSR Manager at Seeed Studio

。

Jointly organize/participate in multi-stakeholder projects/platforms/events/webinars/workshops/hackathons/etc. to accelerate SDGs with local communities and open tech anywhere in the world by connecting with Ye Seong SHIN today on LinkedIn.

。

Seeed Studio is the IoT and AI solution provider for all types of traditional industries’ sustainable digitalization. Since its establishment in 2008, Seeed Studio’s technological products and customization services are used for smart agriculture, smart cities, smart environmental monitoring, smart animal farming, smart aquaculture, meteorological monitoring, STEAM education, and all types of emerging scenarios enabled by the Industry 4.0. With the company’s mission to “Empower Everyone to Achieve Their Digital Transformation Goals” (which shares similar values with SDGs’ Motto of “Leave No One Behind”), Seeed Studio is devoted to using open source technologies for accelerating SDGs with multi-stakeholders from UN agencies, academia, companies, CSOs, governments, public/private organizations, and so on. This is why, Seeed Studio also founded “Chaihuo Maker Space”, and started China’s first Maker Movement by annually organizing “Maker Faire Shenzhen”.